Aromatic Altars, Value Judgements

Hannah Marie Marcus's "Commodity Exchange" at Olfactory Art Keller

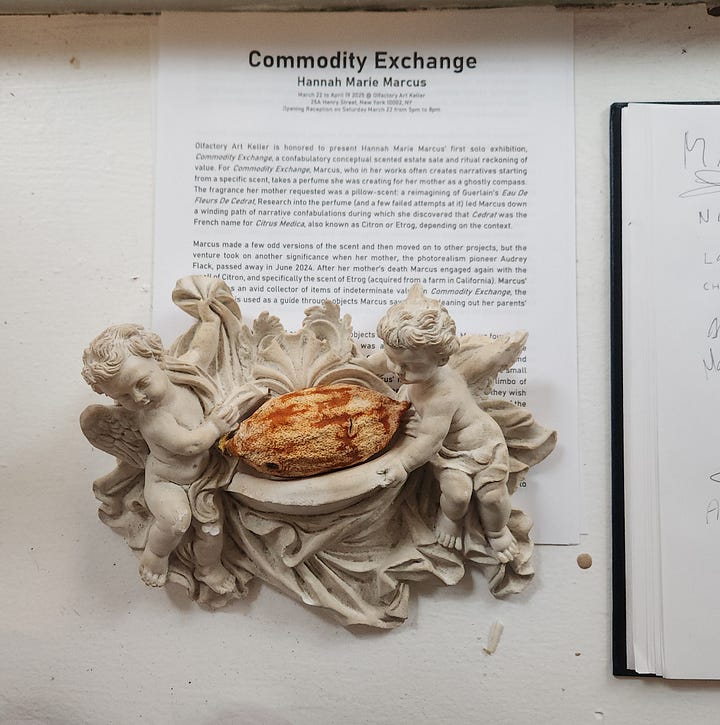

When you step into Olfactory Art Keller to see Hannah Marie Marcus’s Commodity Exchange, one of the first things you might notice is an old-fashioned balance scale standing on a pedestal. It’s a prominent element among the many other objects in the room, due to its centrality and its height; it’s also an apt metaphor for the entire exhibition.

On one side of the scale rests a piece of citrus fruit variously known as a citron, cedrat, or etrog. The fruit’s weight will gradually diminish as it desiccates throughout the run of the show, causing its side of the scale to rise and to allow the opposing object, a small metal trinket box filled with glass eyeballs, to drop lower.

The value and identity of any particular thing shifts over time, due to actual physical change or to our different perceptions of it. What do we “see” (either collectively or individually) in an object that makes us think it is precious or cheap, desirable or disposable? Will a work of art and our ever-evaluating gaze ever achieve perfect balance? We’re left to ponder these questions.

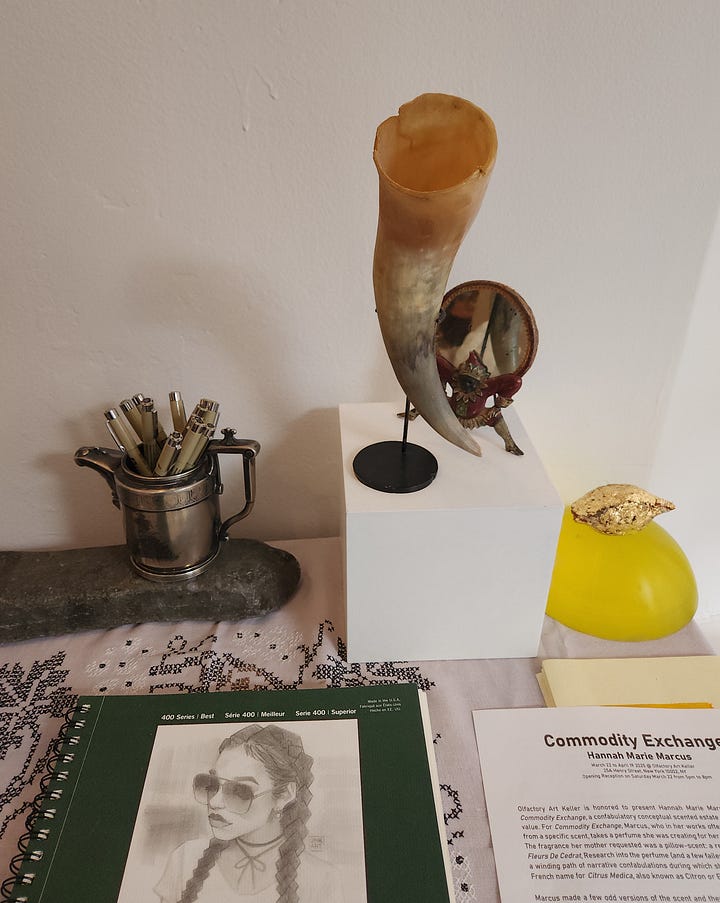

If you wander into Olfactory Art Keller by chance while this show is on view, you might even wonder: is this an artist’s studio, a thrift store, a downtown boutique of small items for the home?

In a sense, it’s all of the above. Hannah has staged Commodity Exchange as “a confabulatory conceptual scented estate sale and ritual reckoning of value” following the death of her mother, the pioneering feminist artist Audrey Flack, and the official cataloguing and dispersal of Flack’s art and archives. For this project, she gathered dozens of other items “which were highly valued by Marcus’ mother but now are in a limbo of undetermined subjective value.”

I went to see Commodity Exchange about one week into its run and stayed a while to observe other visitors. Guests ranged from family and close friends who had known Audrey and/or Hannah for many years, to people who were familiar with Audrey’s career and/or Hannah’s art and music, to strangers who entered the gallery with no previous knowledge of either artist or the content of the installation.

I wove among the clusters of small objects as well as larger assemblages that combined unrelated objects in surprising juxtapositions.

I kept pausing to inspect all manner of bric à brac, tchotchkes, objets d’art — pick your term — from plastic dice to a nineteenth-century inkwell, from an Egyptian shabti figure to a Rococo-style china shepherdess to a celluloid Santa Claus ornament. A grouping along one wall included plaster anatomical models, various deities, a seated Shakespeare, and an action figure of a professional wrestler.

On the back wall of the space, Hannah had arranged a recreation and elaboration of her mother’s medicine cabinet, complete with a toothbrush and a bottle of Guerlain’s Eau de Fleurs de Cedrat, a favorite scent that her mother had asked her to duplicate in her own perfumery. A large-scaled plaster cast of a human nose anchored the display.

A medicine cabinet is a functional space that can turn quite personal—a compact archive of health and hygiene, even a type of self-portrait. Hanging on this wall, in a gallery, lit from within, this cabinet resembled an altar niche or some other kind of display for meditation.

Visitors were permitted, if we wished, to light a votive candle for a silent prayer or intention. We were also informed that the show is collaborative: Hannah invites visitors to assess the “sensory, sentimental, monetary, even ethical” value of the displayed objects and choose one in order to purchase it from the display.

After selecting an item, the visitor makes a donation (in an amount of their own choosing) and writes a brief description of the object and a mention of the piece’s newly determined “value” on a piece of Chinese joss paper.

The visitor sprays their note with one of three citrus scents that Hannah created in her efforts to recreate Guerlain’s cedrat scent for her mother, and then sticks the note to the wall. At the close of the exhibition, all the scented notes will be burned, in a gesture of ancestral worship.

Hannah Marcus was present at OAK to guide visitors through the process; I caught her explaining some of the objects’ origins in this photo. I initially met Hannah through NYC olfactory art circles a few years ago and I’ve been following her work, including a “scent retrieval” seance that she staged at Olfactory Art Keller in October 2023, ever since.

I’ve been aware of Audrey Flack’s art much longer, ever since I was a college student and came across an illustration of her painting Queen (1976) in one of my art history textbooks. A few years later, as an intern at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, I did some basic research on another of Audrey’s works, Macarena of Miracles (1971), from the Met’s collection.

Thanks to Hannah, I met Audrey in person in 2023, and Audrey was kind enough to sign my long-cherished copy of Breaking the Rules: Audrey Flack, A Retrospective (1993). We chatted a bit about shared art-world acquaintances and her longstanding interest in Marian imagery, from Luisa Roldán’s weeping Madonna sculptures (like the one in Macarena of Miracles) to the paintings of Carlo Crivelli.

Remembering this conversation, I chose from Hannah’s installation a small plastic figurine of the Virgin of Guadalupe (pictured above against an illustration of Macarena of Miracles). I made my donation via Venmo, wrote a note about my “acquisition” and the value of money and memory I’d assigned to it, spritzed the paper with Green Citron, and affixed it to the gallery wall. The Virgin is now standing on a windowsill in my home workspace, providing companionship and inspiration.

Commodity Exchange is still open at OAK through April 26, 2025. My friend Quinn has also written a reflection on this show on her own Substack — give it a read!

Closing with the idea of art (and various kinds of “value”) in equilibrium, here’s a quote from Audrey Flack, cited in an article in Smithsonian magazine:

“Great art is in exquisite balance. It is restorative. I believe in the energy of art, and through the use of that energy, the artist’s ability to transform his or her life, and by example, the lives of others.”

And here’s another, from a 2011 interview:

“We will deal more and more with computers and cell phones, but we still have to deal with the fact of our mortality. Nothing does it like art and what we are talking about, that inner calling, that inner recognition of what art does and is. Art helps us live, art can heal, artists restore sense to the world.”

I wish you a restorative week filled with serendipitous moments of art and beauty, however you assign those definitions and values to the world around you.